When most people think of Cicero, they picture him speaking – standing in the open air forum of Rome, or within the closed temple of a senate meeting. When I think of Cicero, I think of him in the library with his books – both reading and writing. In other areas of the humanities, you can read the very words which were written by a certain historical figure in his or her own hand. I recently noticed that my home institution, the University of Southern California, has digitized some of the correspondence of Voltaire, including letters to and from Frederick the Great, King of Prussia from 1740-1786. The Bodleian library has digitized Mary Shelley’s draft of Frankenstein, written in her own hand with edits and revisions in notebooks from 1816.

Although we are lucky to have an incredibly large body of extant works for Cicero, our earliest texts come from manuscripts of a much later period, and we have no equivalent of – for example – the autograph letters of Voltaire. And so, unable to see our sources in their original materiality, for a long time Classicists have approached texts in a disembodied form. Recently there has been a real push towards considering ancient literature in the context of the cultures of book-making and reading, with the rise of papyrology as a discipline contributing substantially to this research.

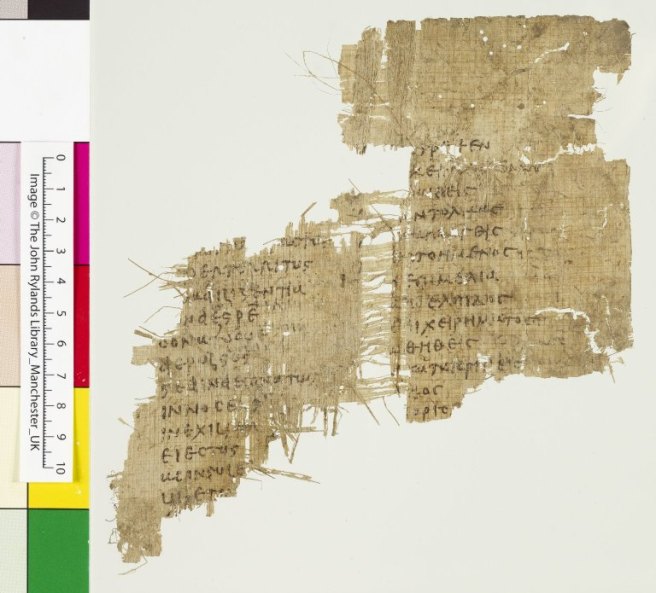

One of the issues that we face when we want to look at manuscripts and papyri containing ancient texts is the fact that the originals are kept in all sorts of institutions all over the world, each with different policies concerning access and digitization. In order to even know where these things are takes a bit of effort, honestly. Papyrologists are usually excellent about cataloguing and sharing information, and have many online databases that help you find things. For literary papyri, you can use the Leuven Database of Ancient Books (although this also includes parchment) and Cedopal. There are Cicero papyri in at least Durham (North Carolina), Vienna, Florence, Cologne, London, Manchester, and Giessen. With such a state of affairs, digitization becomes increasingly important, although, as we shall shortly see, it comes with its own complications. Consulting a transcription of the papyrus without seeing an image is not really enough – this became clear to me when I looked at the marginalia of one of the Rylands papyri, which are hard to transcribe in a way which shows where exactly the text appears on the page. Looking at transcriptions, such as the following from Cavenaile’s Corpus Papyrorum Latinarum (CPL), gives you a very disembodied sense of what the papyri look like:

Almost all of the Ciceronian papyri come from significantly later than his own lifetime (106-43 BCE). We’re dealing with Ciceronian texts which were used in contexts and formats subsequent to late Republican usage. The majority come from the 4th and 5th c. CE, with one (in Giessen) coming from the 1st c. CE. The two papyri which I saw are dated to the 5th c. CE – P. Ryl. 1.61, a Latin to Greek vocabulary list which corresponds to In Catilinam 2.14-15, and P. Ryl. 3.477, containing Divinatio in Caecilium 34-37, 44-46 with both Greek and Latin marginal comments on the text. Both of these papyri came from Egypt, and both were codices rather than book rolls. All of the extant Cicero papyri are oratorical, with many containing the Catilinarians and the Verrines; all of the Ciceronian papyri contain works which are more fully represented in medieval manuscripts. P. Ryl. 1.61 was used by a Greek speaker who was learning Latin with Cicero’s Catilinarians; P. Ryl. 3.477 was used by someone interested in the legal issues underlying Cicero’s case against Verres. P. Ryl. 3.477 contains the longest extant marginal note on papyrus (McNamee). The Cicero papyri are also of interest to us since they demonstrate bilingualism by inhabitants of the Empire during Late Antiquity; we get the sense that even in 5th c. CE Egypt, there was something of value in Latin for non-Romans (Sánchez-Ostiz).

The John Rylands Library in Manchester contains a number of important ancient materials, including a Greek papyrus fragment from the Gospel of John (pictured above). The library was founded by Enriqueta Rylands in memory of her husband John Rylands. My guide at the library told me that on International Women’s Day, all of the male statues in the historic reading room (also pictured) were covered over with the statue of Enriqueta remaining visible in order to highlight her agency in creating an imposing intellectual space.

It was raining heavily on the day in late June when I visited the John Rylands Library. Special Collections – a series of desks with book cradles and power outlets – was mostly empty, but there was a lively buzz of activity. Pairs of researchers and scholars spoke rapidly to their partners in low tones, and the staff whispered to one another. My inspection of materials was punctuated by a man behind me muttering “five pounds five shillings” – “June 22nd 1916” – “London”. I had to document myself – present a passport, proof of address – and then the papyri I had summoned were signed out to me. The John Rylands allows photography for personal use but forbids their promulgation. I took many personal photos, but the ones you see in this blog post are those which are officially released by the John Rylands. The two papyri which I looked at had already been digitized by the library, and can be accessed online for free. Most of the other patrons in the Special Collections were using materials which they could handle directly, but the Ciceronian papyri are mounted to glass. Each papyrus, encased in glass, is given to the reader on a foam tray, so that you can flip it and observe both sides.When the librarian handed me the first fragment, I asked about the conditions in which the glazed papyri were kept; one, the smaller of the two, was kept in a flight case (P. Ryl. 1.61); the other was kept in a paper box. Both were stored in a secure room which could have the oxygen removed from it in case of a fire. As I took close-up pictures of the different elements of the papyri, I appreciated one reason why the library would forbid private photographs to be disseminated – the surface of the glass means that details were obscured by the glare of the overhead lights, and by my reflection. As I looked at the papyri, I had the transcription from Cavenaile (CPL) open on my laptop so that I could orient myself in the text, and I also looked at the digitized images from the John Rylands website. Since the photo image of P. Ryl. 3.477, containing the Divinatio in Caecilium, was produced, the papyrus has been rearranged in its glass frame; and you can also see by comparing the original with its digital copy that parts of the papyrus which were once one piece have started to come apart. I noticed that the colour of the papyrus itself was darker in the photograph; as it turns out, the papyri at the Rylands have recently been through certain processes of conservation, which have left them a lighter colour. The papyrus itself, then, looks different from its image, and it is only this image that most people will ever be able to see. This is one of the interesting issues when dealing with ancient materials – they continue to have a life even after they have been made static by reproduction.

Further reading: “Cicero” in Texts and Transmission, ed. Reynolds (1983); McNamee, Annotations in Greek and Latin texts from Egypt (2007); Sánchez-Ostiz, Cicero Graecus: Notes on Ciceronian Papyri from Egypt, ZPE 187, 2013 pp144-153; many chapters of interest in The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology, ed. Bagnall (2009).