The 2017 meeting of the Society for Classical Studies that took place from Jan. 5th-8th in Toronto had a common thread running through it: a growing interest among classicists to engage wider audiences through outreach, digital technologies, and social projects. But this desire to move beyond the traditional limits of classical research and pedagogy was also marked by internal anxieties regarding the field’s future, and what kind of role classicists should have in the current political climate.

At “The Impact of Immigration on Classical Studies in North America”, the first speaker was supposed to be Dan-el Padilla Peralta (Princeton), whose 2015 autobiography – Undocumented – describes his experiences as a Dominican living in the US without legal documentation who worked his way to a Classics degree from Princeton, and the subsequent life of a scholar. Ironically, Peralta wasn’t able to be in Toronto to give his paper — for immigration reasons. James Uden (Boston University), one of the panel’s organizers, stepped in to read out Peralta’s paper, noting that even under normal circumstances, reading someone else’s paper is a strange thing, but that this case felt stranger, given the intimate nature of its content.

https://twitter.com/opietasanimi/status/817807008187420672

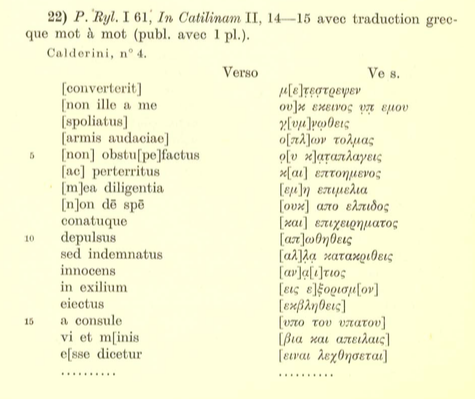

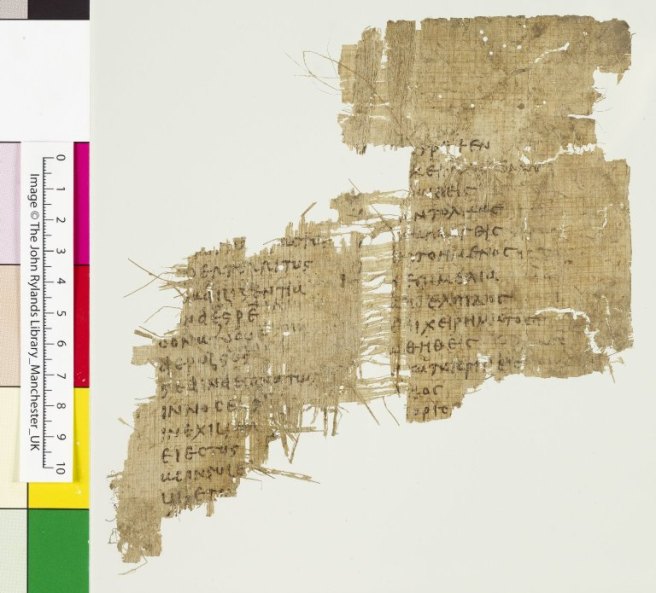

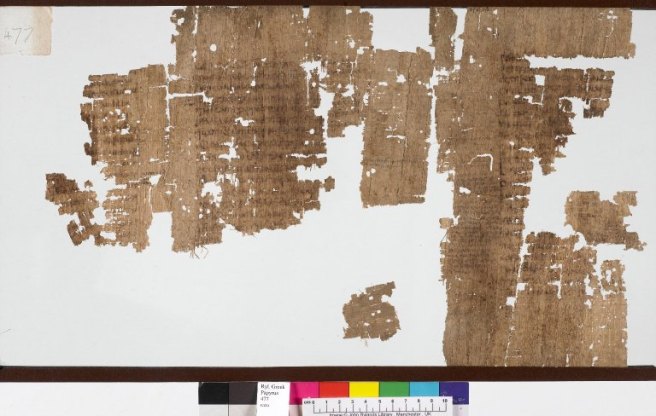

In 2015, Peralta published a two-part piece in Eidolon entitled “Barbarians Inside the Gate” (part I, II), which discussed the ancient parallels to – and influences upon – the modern problem of immigration in the US. One of the recent cooptations cited by Peralta is Ted Cruz’s assimilation of himself to Cicero with Obama as his Catiline in the context of then POTUS’ proposed immigration reform, an incident that I first saw written about by Jesse Weiner in the Atlantic in 2014 (“Ted Cruz: Confused about Cicero“). By casting himself as a modern day Cicero, Cruz had unwittingly (?) made a threat of violence against the “Catilinarian” President. Peralta went on to describe the privileged positions of scholars – traveling for research and conferences without having to consider any threat to their immigration status, or being turned away at the border (obviously given poignance by his own absence). Citing this passage from C. Rowan Beye’s contribution to Compromising Traditions (1997) —

— Peralta argued that a problematic and artificial distinction was being made between privilege of academics (prized for their foreignness – if it was the right kind) on the one hand, and undocumented workers on the other. Poised on the edge – now – of the political threat to the undocumented in the US, including our own students, this categorization of “good immigrant”/”bad immigrant” enforces value judgements upon human beings, impeding their mobility, settlement, and health – both mental and physical. The second speaker of this panel, Ralph Hexter (UC Davis), described the shape of immigration in California, the state with the highest number of immigrants: 10 million, of whom many are now citizens or residents, but 25% are undocumented. In California, undocumented students who have graduated from high school have access to higher education, but no access to federal loans. Through the DREAM act, undocumented students would be able to find federal work study or student loans, and individual states could decide to provide financial aid to such students. But, as Hexter pointed out, the incoming POTUS used the repeal of the DREAM act as one of his campaign slogans; and now undocumented students everywhere are fearful for their future. Hexter noted that for many students, the question of immigration will be an enormously personal issue. Hexter moved on to demonstrate how discussions of canonical classical texts could accommodate discussions of these issues. Classicists use texts capable of plurality of perspective – “immigrant, host national, universal order”:

Hexter suggested the Aeneid as a text with which to explore the problem of immigration: refugees leave a destroyed city (Troy); family, central to the problem of immigration, is central to the epic; Turnus’ hostility can be read as a hostility to new migrants. Hexter even cast Virgil’s Evander as Canadian Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, to Obama’s “well meaning but weak willed Latinus” – likening Dido to Angela Merkel, who left her border open to Syrian refugees. Hexter also invoked Luis Alfaro’s play – Mojada: A Medea in Los Angeles – which combined the tragedy of the Ancient Greek Medea with the trauma of modern day Mexican immigration. The title “Mojada” is the Spanish slang equivalent to, and containing as much emotive force as, the English “wetback” – used to describe the undocumented who supposedly arrive in the US “wet” (mojado) because of crossing borders by water. During the Q&A section of Hexter’s talk, a member of the audience brought up Canadian playwright Olivier Kemeid’s L’Eneide, which explicitly brings out immigration as a central crisis of Aeneas’ tale.

Looking to classical texts as a means to remediate modern social problems was a thread that connected the “Impact of Immigration” panel and the “New Outreach and Communications for Classics” panel. At the Outreach panel, Roberta Stewart (Dartmouth) spoke about her experiences talking through Homer with combat veterans in New Hampshire (which has an 8% vet population), a project funded with an NEH grant. “Talking through” is a better way to describe what she does than “teaching” – she stressed in her paper that the aim of the sessions was to facilitate discussion, rather than to use a hierarchical teaching model:

Outreach in this case, Stewart says, means giving texts an environment of relatability, where expertise is not required. In fact, when veterans use Homer to work through issues of war, homecoming, and trauma, it is they who are the experts. Stewart’s project makes veterans the authors and authorities in designing curriculum for veterans. It’s not exactly that “reaching out” in such a way removes the expertise of the classicist who is there to facilitate – what became clear over the arc of this SCS panel is that the public wants an “expert” to be in the room, to guide things, to lend some weight to proceedings. But working with a text in such a way allows the reader to find the meanings which are most resonant and – in this case – healing. In the current climate, changing what it means to be an “expert” is an important shift: expertise moves from the top-down to something more open.

Another strong point that came from this panel is the necessity for outreach to be pluralistic. There are a lot of different kinds of audiences to reach out to. The implication here is that the centre is the academy, which normally looks inward to itself and its own initiated members. From the Paideia Institute, we heard about several projects: Jason Pedicone presented on the Legion Project, which connects classicists working outside of academia – including tracking those who have PhDs in Classics but did not find scholarly positions; and Liz Butterworth on Aequora, teaching literacy to elementary and middle school students with Latin. Christopher Francese (, Dickinson College) described a number of outreach projects he’s involved with: a Latin club for children from Kindergarten to Middle School; blogging; podcasting. Francese’s podcast is a series of 5-10 minute recordings on Latin metrics and poetic performativity.

The outreach panel, while describing ways to open up classics to wider audiences, also brought up some of its inherent tensions. As I was live tweeting Francese’s comments on podcasting, multiple podcasters on twitter spoke to me to say: We’re here, and we’re doing this work. In the days after the conference, I was discussing with these podcasters – Aven McMaster (), Alison Innes (), and Ryan Stitt () – the issue of in-groups and out-groups. These podcasters know each other well, are well known by their own audiences, but not that well known by the “professional” arm of the discipline. During the outreach panel, one member of the audience – a high school Latin teacher – drew attention to the fact that there was a weak relationship between school teachers and classicists in universities. And, given the fact that declining enrollment in classics is a serious issue, the apparent lack of interest in the teachers – on the front lines of training future classicists – was part of this problem. After the conference it became clear to me that it wasn’t the case that classical resources weren’t available on the internet, but that lack of centrality meant that they were difficult to get to know about, unless you were already part of a certain group. An antidote to this problem will involve those who do have a wide audience, in real life and on the internet, engaging in some signal boosting – letting those within and outside of the academy know what kind of projects are out there. The SCS has started an effort to review digital projects; see, for example, their review of The Latin Library.

Digital classics was also well represented, thanks to the “Ancient MakerSpaces” workshop, run by Patrick Burns (@diyclassics, ISAW). This workshop attracted the majority of live tweeters (for obvious reasons), and so is well documented in the twitter record of 2017’s SCS. The success of this workshop came not only from the content of its presentations, but its format – which eschewed the traditional Q&A, opting instead for interactive demonstrations. The digital humanities presentations seemed to have a deep connection with pedagogy:

Thomas Beasley (Bucknell University), demonstrating the visualization of networks in the ancient mediterranean, noted that his tool could improve spatial literacy in undergraduates, who often find it difficult to come to terms with the geography of the mediterranean. In the outreach panel, Sarah Bond (, University of Iowa) had talked about how maps are always useful in teaching contexts. Bond demonstrated that the spatial visualization had been a part of enhancing engagement since at least the 16th century, when Protestants used maps to illustrate the Bible, to great popularity. Digital tools also allow a larger degree of participation. Rodney Ast (University of Heidelberg) demonstrated how anyone could suggest editorial changes to papyri entries in the Digital Corpus of Literary Papyri – during the course of his presentation, he edited a database entry for a Ptolemaic ostrakon to include the fact that it contains a quotation from the Odyssey:

https://twitter.com/opietasanimi/status/817740442762616833

Questions of digitization and information technology were present in other areas of the conference as well. This year’s Presidential Panel – “Communicating Classical Scholarship” – included presentations from Sebastian Heath (, NYU) on digital publishing through ISAW; Fiona MacIntosh (Oxford University) on the APGRD‘s (@APGRD) ebooks of the Medea and the Agamemnon, in which archival footage of performance reception are embedded in the books’ “pages”; and Erich Schmidt (University of California Press) on the future of scholarly publishing, including discussion of how expensive it is to print monographs. This panel betrayed some of the tension and anxiety felt by classicists regarding their digital futures, but also regarding their print past. When comments were made by panelists suggesting the general preference of scholars for print books, there were scatterings of applause from the audience. Essentially, we are not of one mind when it comes to digital humanities, or the future of how scholarship is disseminated – and that includes the role of social media. We’re not on the same page, either, on whether or not these new trends have value, or whether they can be counted among a scholar’s contributions to the field. This much is made clear by the fact that the SCS has a statement asking that classics departments take digital and technological projects into consideration when they consider a candidate’s value:

A final project to draw attention to is the new Classics and Social Justice group organized by Dan-el Padilla Peralta, Amit Shilo (UC Santa Barbara), Roberta Stewart, and Nancy Rabinowitz. This group is bringing together scholars and teachers who want to use their classical expertise to help address current social problems: many of the attendees of the first meetings have already done work of this kind, whether has meant reading Homer with veterans, bringing classics into prisons, or addressing the issue of immigration. The evening meeting on Jan 7 was broadcast on Facebook live, and the resulting video can be watched here. The existence of this group demonstrates a growing trend among classicists to integrate the intellectual part of their lives with action and advocacy, and to bring their intellectual energies into spaces outside the limits of the traditional classroom. Among the aims of this new group is to draw attention to the fact that many scholars have already been doing this kind of work some time – invisibly – and to bring together those with similar ideas, to be a resource to one another and to others.

https://twitter.com/opietasanimi/status/817757524506120197