In February for Black History Month, I had a daily practice of posting to Bluesky on the hashtag #AncientBlackness, where I shared resources on ancient representations of blackness, the work of Black classicists, and Africana receptions. I took some time every morning before work to collect some pieces from my teaching and research over the last few years, inspired by the work of the many colleagues and collaborators who are cited throughout. Read the full thread here:

For #BlackHistoryMonth this year, I’m going to be posting daily about: representations of blackness in Greco-Roman antiquity, the history of scholarship by Black classicists, and the history of Africana receptions using the hashtag #AncientBlackness. Join me. https://bsky.app/profile/opietasanimi.com/post/3lh4p2jjnjc22

Many of my examples will come from what we have called the “classical” tradition, but I encourage people who work on global antiquities to contribute to #AncientBlackness as a hashtag.

This thread follows Sarah Derbew’s (2022) practice of using the lower case (“black,” “blackness”) to refer to antiquity, and the upper case (“Black,” “Blackness”) to refer to modernity. #AncientBlackness https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/untangling-blackness-in-greek-antiquity/5520140757B8E3C8CD5EA8BD4CAFD8A4

Racist projections have historically shaped the study of ancient blackness, but disaggregation of terms shows that the concept is historical (i.e., black people existed in antiquity) but not transhistorically stable (i.e., “blackness”/“Blackness” depend upon historical context). #AncientBlackness

There is an abundance of representation of blackness in the Greek and Roman artistic record. Frank M. Snowden, Jr. (1911-2007) painstakingly collected objects (and texts) representing #AncientBlackness, but his work was never fully metabolized by the mainstream of classical scholarship.

Patrice Rankine (2011: 53) has noted that “The many wonderful images of ‘blacks’ in antiquity that grace the pages of Snowden’s books tend not to find their way into textbooks on Greek art” https://academic.oup.com/book/3616

In 2022, Najee Olya, conducting an overview of how Greek representations of black Africans are systematically omitted from museum displays and art survey textbooks, stated that “Rankine was correct ten years ago, and still is now.” #AncientBlackness

With that in mind, today’s object is an Attic amphora (c. 535 BCE). One side represents Memnon, King of Aethiopia, in the style of a generic Greek hero while his attendants are figured as Aethiopian fighters. British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) #AncientBlackness https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1849-0518-10

Image: British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

[2] Memnon as King of Aethiopians appeared early in the Greek literary record. The now lost Aethiopis–part of the ancient Epic Cycle which told the story of the Trojan war–told the story of Memnon and Aethiopians coming to help the Trojans. #AncientBlackness https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aethiopis

Homer’s Odyssey begins (1.22-26) with the god Poseidon feasting and spending time with the blessed Aethiopians at the remote edge of the known world. At the end of the Iliad (23.206), Iris tells the winds that she must return to the sacred feast in Aethiopia. #AncientBlackness

In Blacks in Antiquity, Frank M. Snowden, Jr. (1970: 144) notes the presence of Aethiopians in the ancient imaginary as early as Homeric epic. Aethiopia is referenced 3x in the Odyssey (1.22-26, 4.84, 5.282-287); 2x in Iliad (1.423, 23.206) #AncientBlackness https://www.google.com/books/edition/Blacks_in_Antiquity/37MTRCr9oAUC?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover

Homer tells us that Olympians were fond of visiting the Ethiopians, where he remained for twelve days. Poseidon also visited the distant Ethiopians to receive a hecatomb of bulls and rams. At the end of the Iliad Iris informs the winds that it is not possible for her to remain but that she must return to the streams of Ocean in order to participate in a sacred feast offered by the Ethiopians. Hence, the goddess makes a special trip alone.

Snowden 1970: 144

In the spring of 1977, Romare Bearden’s Odysseus collages premiered at Cordier & Ekstrom Gallery on the Upper East Side, New York. Albert Murray described Bearden’s Odysseus series as a “visual equivalent of the blues.” #AncientBlackness

In “Inscription at the City of Brass,” an interview with Charles Rowell (1988: 428-446), Romare Bearden said that Poseidon “always has to come up from Africa, where he wants to be with his friends there.” #AncientBlackness https://www.jstor.org/stable/2931510?origin=crossref

[3] There are many ancient words for what is today called Africa. Greek sources typically referred to ⅓ of the known world as “Libya” (e.g., Herodotus 4.45; 5th c. BCE). Romans also used the term “Africa”: the earliest attestation in Latin is in the poetry of Ennius (3rd-2nd c. BCE) #AncientBlackness

Ancient sources speak of Aethiopia as a mythical/imaginative landscape as well as a physical location spanning the south of modern Egypt and north of modern Sudan (Derbew 2022: 12, cf. 98, 168). Αἰθίοψ/Aethiops also appears as a generic term for a black person #AncientBlackness

The term “Aethiopian” (Greek: Αἰθίοψ [Aithiops], Latin: Aethiops) combines two Greek words: αἴθω [aithō] “I burn,” “I blaze” + ὄψ [ops], “face.” Sarah Derbew (2022: 14) emphasizes the concept of “blazing” (i.e., bright, shining heat) over simply “burning” in its etymology #AncientBlackness

Greek writers also used the color term “black” (μελάγχιμος [melangchimos], μελάγχρως [melangchrōs] of a variety of peoples including Egyptians, Indians, and Aethiopians (Derbew 2022: 14, cf. 172). Romans also used Latin color terms for “black” or “dark,” e.g. fuscus #AncientBlackness

Asclepiades (Anth. Pal. 5.210.3-4; 3rd c. BCE) praises a woman called Didyme for her radiant blackness: “And if she is black (μέλαινα [melaina]), what difference to me? So are coals but when we light them, they shine like rose-buds,” translated by Snowden (1970: 178-179) #AncientBlackness

εἰ δὲ μέλαινα, τί τοῦτο; καὶ ἄνθρακες· ἀλλ᾽ ὅτε κείνους

θάλψωμεν, λάμπουσ᾽ ὡς ῥόδεαι κάλυκες.“And if she is black (μέλαινα [melaina]), what difference to me? So are coals but when we light them, they shine like rose-buds”

Asclepiades (Anth. Pal. 5.210.3-4).

Translated by Snowden 1970: 178-179.

From the Roman period, a graffito written in Latin similarly praises a black woman as a source of amatory radiance (CIL 4.6892): “whoever loves a bright black woman burns with black coals,” translated by Haley (2009: 47) #AncientBlackness https://pressbooks.claremont.edu/clas112pomonavalentine/chapter/haley-shelley-1993-black-feminist-thought-and-classics-re-membering-re-claiming-re-empowering-in-feminist-theory-and-the-classics-edited-by-nancy-rabinowitz-and-amy-richlin/

Quiquis amat nigra(m) nigris carbonibus ardet.

Graffito (CIL 4.6892).

Nigra(m) cum video mora libenter ed<e>o

“Whoever loves a bright black woman burns with black coals. When I see a bright black woman, I gladly eat blackberries.”

Translated by Haley 2009: 47.

Bonus for today, as I’m in the office and can share some of the books I’m drawing on for the daily #AncientBlackness posts (we will discuss Snowden’s view of blackness as “before color prejudice”)

[4] Terminology is a fraught issue in the history of the study of #AncientBlackness. The problem is ultimately rooted in the fact that scholarship on (and museum curatorship of) ancient objects representing blackness have historically projected modern racial politics onto Greco-Roman antiquity.

Sarah Derbew treats this issue thoroughly in her recent book, Untangling Blackness in Greek Antiquity (2022), but discussed the problem as early as 2018 in a blog for the Getty: “An Investigation of Black Figures in Classical Greek Art.” #AncientBlackness https://www.getty.edu/news/an-investigation-of-black-figures-in-classical-greek-art/

In this blog post, Derbew (2018) presents an analysis of museum labels and secondary scholarship, demonstrating the ways in which didactic labels and catalogue descriptions have been informed by racial assumptions deeply rooted in the history of the transatlantic slave trade.

One object discussed by Derbew (2018) is a janiform drinking cup (c. 510-480 BCE) currently in the Boston MFA which has been interpreted to represent two female faces. #AncientBlackness https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153959

Derbew’s book (2022) argues that these kinds of janiform cups assert a relationship between brownness and blackness, not a contrast between “whiteness” and blackness. Yet the didactic on the Boston MFA website *still* aligns Greekness with whiteness (“white, i.e. Greek”) #AncientBlackness https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153959

DESCRIPTION The joining of black and white female heads is unusual. On black-figure vases, white (i.e. Greek) women are often painted with the same white slip (liquid clay) as that used on the mouth of this cup, but on head vases they are always left in the reddish and the more lifelike color of the clay, heightened somewhat by a wash of yellow ochre, so the flesh is red, eyes white, and the iris black. The African woman smiles with her teeth showing; her eyes and eyebrows are white. Her hair is a mass of dots, with traces of red paint. [https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153959]

The Boston MFA didactic ^ also heavily privileges the so-called “white” side of the janiform cup; a significant privileging given the fact that the whole point of such cups is a form of dialogue #AncientBlackness

In response to the #BLM movement in summer 2020, the Getty published another blog post by Paula Gaither et al., “Rethinking Descriptions of Black Africans in Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Art.” These posts were made in 2018 and 2020, but many museums have not updated language #AncientBlackness https://www.getty.edu/news/rethinking-descriptions-of-black-africans-in-greek-etruscan-and-roman-art/

One of the objects discussed by Gaither, et al., is an object long catalogued as a “Portrait of an African Boy.” As the object is ungrounded (to use Marlowe 2013’s terms), identification as “African” relies on perception, not historical context #AncientBlackness https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/103SV7

This object is also @maggiecknapp.bsky.social‘s pick for today’s contribution to #AncientBlackness

While thoughtfulness (esp. in regards to “ungrounded” material culture) is particularly needed in the analysis of such objects, unclassifying ancient objects formerly identified as representations of “Africans” may also have the unintended effect of “white-washing” antiquity… #AncientBlackness

[5] @maggiecknapp.bsky.social‘s contribution to #AncientBlackness today is one of my favorite ancient images and one which I use in almost all of my courses (not just ancient race, but, e.g., Roman civ courses). CC-BY-SA-3.0 (Sailko): https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Didone_tra_ancelle_e_personificazione_dell%27africa,_mentre_si_allontana_la_nave_di_enea,_da_casa_di_meleagro,_8898.JPG

As @maggiecknapp.bsky.social notes, interpretations have been speculative, often without considering contextual ancient evidence. Three women in the foreground may together represent a Roman view of Africa #AncientBlackness

Ship in the top right corner is like the ship in other contemporary frescoes of Ariadne, abandoned by Theseus. Aeneas’ abandoning of Dido in Vergil’s Aeneid draws on Ariadne myth. The fresco ^ seems to combine these literary allusions. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f2/Abandoned_Ariadne_fresco_from_Casa_di_Meleagro%2C_Pompeii.jpg

As such, this fresco might be a representation of Aeneas abandoning Dido. By this reading, the central figure becomes Dido, Queen of Carthage, flanked by two women who allegorize Africa. #AncientBlackness

The romance between Dido and Aeneas in Vergil’s Aeneid is explicitly described as a denial of African courtship. In Bk 4, King Iarbas, King of Gaetulia, prays to Jupiter in anger at Dido’s preference for Aeneas as a foreign suitor #AncientBlackness

As @maggiecknapp.bsky.social notes, elephant headdresses are a standard visual marker for “Africa” in Roman art. Here, e.g., Hadrian’s gold coin showing the submission of personified Africa, a woman with elephant headdress #AncientBlackness https://bsky.app/profile/maggiecknapp.bsky.social/post/3lhfug3om5s24

Scholars have increasingly viewed Dido as a racialized figure. The most famous and influential treatment is by Shelley P. Haley (2009) “Be Not Afraid of the Dark: Critical Race Theory and Classical Studies” #AncientBlackness https://ms.fortresspress.com/downloads/0800663403_Chapter%20one.pdf

More recently, we have Elena Giusti’s (2023) “Rac(ializ)ing Dido” #AncientBlackness https://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/id/eprint/180780/

[6] Yesterday, I briefly referenced a famous piece by Shelley P. Haley, whose contributions to the study of blackness in antiquity were profound for classics and premodern race more generally. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shelley_Haley #AncientBlackness

Shelley P. Haley’s critical research has applied intersectional lenses to the Greco-Roman representations of “foreign” women whose gender is racialized: Sophoni(s)ba (1990), Cleopatra, Dido, and Scybale (1993, 2009), and Medea (1995). #AncientBlackness

Haley’s research has been wide-ranging, incorporating Black feminist theory into classics pedagogy, as well as addressing the role of African American women, such as Fanny Jackson Coppin (1837-1913), in the discipline of classics #AncientBlackness https://www.google.com/books/edition/Reminiscences_of_School_Life_and_Hints_o/zMMQAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0&bsq=Shelley%20Haley,%20Fanny%20Jackson%20Coppin,%20Reminiscences%20of%20School%20Life,%20and%20Hints%20On%20Teaching,%20Volume%208%20of%20the%20African%20American%20Women%20Writers%20Series,%201910–1940

More recently, Haley contributed a chapter to Denise McCoskey’s edited volume, “A Cultural History of Race in Antiquity” (2021), on the relationship between race and gender in antiquity #AncientBlackness https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/cultural-history-of-race-in-antiquity-9781350299979/

In 2021, Haley gave a lecture for the first @acmrs.bsky.social RaceB4Race conference to include classicists alongside scholars of premodern race, “Re-imagining Classics: Audre Lorde was Right” #AncientBlackness

In this lecture ^, Haley discusses Audre Lorde’s recollection of the violence of the Latin instruction in “Zami” (1982) by the monsignor, Father Brady, who did not want to teach Latin to Black children. The lowercase “latin” is a deliberate poetic resistance #AncientBlackness https://youtu.be/B7sUaGWDiWc?t=1376

I did not care about his lechery but I did care that he kept me in every Wednesday afternoon after school to memorize latin nouns. … I came to loath Wednesday afternoons, sitting by myself in the classroom trying to memorize the singular and plural of a long list of latin nouns and their genders. Every half-hour or so, Father Brady would look in from the rectory and ask to hear the words. If I so much as hesitated over any word or its plural, or said it out of place on the list, he would spin on his black-robed heel and disappear for another half-hour or so. Although early dismissal was at 2pm, some Wednesdays I didn’t get home after four o’clock. Sometimes on Wednesday nights I would dream of the white, acrid-smelling mimeograph sheet: agricola, agricolae, fem., farmer. Three years later when I began Hunter High School and had to take latin in earnest, I had built up such a block to everything about it that I failed my first two terms of it.

Passage from Audre Lorde’s Zami (1982: 60), quoted and discussed by Shelley P. Haley in her RB4R lecture (2021)

In 2021, Haley gave the Adam Parry and Anne Amory Parry Lecture at Yale and remarked on her own experiences of racialized gender within the field of classics #AncientBlackness:

One of the most frustrating questions I have received throughout my career is: ‘Which oppression has hindered you more in classics? Racism or sexism?’ The prescient work of the Combahee River Collective in their statement, and the advent of critical race feminist theory has helped me and other Black indigenous women of color formulate responses which deconstruct such questions and reconstruct the totality of our limited experiences. One such reconstruction is the concept of racialized gender. In discussions about systemic oppression, the broader framework of racialized gender can be specified as gendered racism or racialized sexism

Shelley P. Haley Yale lecture (2021)

Haley’s work anticipated many of classics’ contemporary concerns. E.g., Haley 1995 emphasizes Morrison’s warning not to see classical reception as the only way in which Afro-American literature can gain value #AncientBlackness https://classics.domains.skidmore.edu/lit-campus-only/secondary/Morrison/Haley%201995.pdf

I undertake the comparison of a canonical piece of Western literature (Euripides’ Medea) and a masterpiece of the literature of an oppressed people (Morrison’s Beloved) with some unease. Morrison’s own warning reverberate in my head: “Finding or imposing Western influences in/on Afro-American literature has value, but when its sole purpose is to place value only where that influence is located it is pernicious.” [=Morrison 1989: 10] As a traditionally-trained classicist, it is tempting to do such comparative work and easy to slip into the trap Morrison describes. As a Black feminist it is a political act to resist the pernicious aspects of the work.

Haley 1995: 177

[7] Haley (1993, 2009) also addressed an understudied ancient text called Moretum, a short mock epic once attributed to Vergil. This poem tells the story of a poor farmer, Simulus, making a modest meal, the cheese-herb dish called moretum, with an enslaved African woman, Scybale. #AncientBlackness

Haley (2009: 42): “needless to say, the Moretum is not now part of the classical canon, but recently whenever the racial composition of ancient Greece or Rome is discussed, scholars always find it.” #AncientBlackness https://pressbooks.claremont.edu/clas112pomonavalentine/chapter/haley-shelley-1993-black-feminist-thought-and-classics-re-membering-re-claiming-re-empowering-in-feminist-theory-and-the-classics-edited-by-nancy-rabinowitz-and-amy-richlin/

The two figures of Moretum, Simulus and Scybale, both have “parody” names of mock epic: Simulus = “snub-nosed” (Greek σιμός [simos]; an adj used of Aethiopians by Xenophanes); Scybale = “trash,” “excrement” (σκύβαλον [skybalon]). But only Scybale’s physical appearance is described #AncientBlackness

The description of Scybale (lines 31-35) identifies her as “African in race” (Afra genus), with “her whole form a testimony to her country” (tota patriam testante figura). The following parts of her body are listed: hair, lips, skin color, chest, breasts, stomach, legs, feet #AncientBlackness

Scybale is described as “dark in color” (fusca colore); a similar Latin phrase (colore fusco) is used by Suetonius (Life 5) to describe Terence the African (Terentius Afer), a formerly enslaved poet from Carthage who wrote Roman comedies #AncientBlackness

Scybale is also identified in the poem as a famula (line 91), one of several Latin words for “slave.” The Romans themselves derived famulus/famula from the Oscan word for an enslaved person, famel. The word familia (“household,” i.e. including slaves) derives from this #AncientBlackness

Haley’s major contribution to discussion of this poem was revealing how modern translations of this text had leaned into (indeed: overemphasized) the language of racial caricature. #AncientBlackness

While clearly racecraft is at work in this ancient poem, modern translations insensitively assented to its premise while adding further prejudice. Haley particularly critiques the translations of Frank Snowden (1970) and Lloyd Thompson (1989), and offers her own new translation (2009: 42) #AncientBlackness

I provide the Latin and my translation of the description of Scybale. It is important to note that most translations of this piece have been done by men influenced by stereotypical descriptions of the physique of African women. Consequently, I have deliberately made my rendering as sensitive to black-feminist and female-empowering concerns as the Latin will allow:

Erat unica custos,

Afra genus, tota patriam testante figura,

torta comam, labroque tumens et fusca colore,

pectore lata, iacens mammis, compressior alvo,

cruribus exilis, spatiosa prodiga planta. (Moretum 31–35)“She was his only companion, African in her race, her whole form a testimony to her country: her hair twisted into dreads, her lips full, her color dark, her chest broad, her breasts flat, her stomach flat and firm, her legs slender, her feet broad and ample.”

Haley 2009: 42

Essentially, Haley identified a textual equivalent to the problem of terminology which Derbew and Olya have more recently addressed. With translation: how can scholars “correctly” render ancient racial language without doubling down or assenting to it? #AncientBlackness https://bsky.app/profile/opietasanimi.com/post/3lheajyipjs2o

Haley (2009: 41) particularly critiqued Snowden (1970: 9), who stated: “The author of the Moretum, who described Scybale, would be rated today as a competent anthropologist.” Najee Olya (2021) has also recently critiqued Snowden for placing Scybale into an objectifying anthropology #AncientBlackness

It’s important to pay attention to these critiques of Snowden because mainstream classicists either ignore his work completely, or else put a footnote into their work generally gesturing to his–not knowing or really caring that his own methods might need updating #AncientBlackness

[8] Black African figures appear across Latin literature from its beginning. Plautus’ Poenulus describes Giddenis’ blackness as well as her beauty (1112-13); Terence’s Eunuchus refers to a “little slave girl from Aethiopia” (165-7); and Terence himself is described as black by Suetonius (Life 5).

Haley’s attention to Scybale in the Moretum was an attempt to redress prejudicial scholarly interest in the character’s objectification. However, few scholars of Latin literature paid close attention to Haley’s intervention #AncientBlackness

In “The Moretum Decomposed” (2001: 418), Nicholas Horsall referred to the presence of Scybale, an enslaved African woman in Italy, as “an impenetrable mystery.” This piece was reprinted in a recent collection, “Fifty Years at the Sibyl’s Heels” (2020) #AncientBlackness

A recent article by Franceca Bellei (2024) gives a fresh treatment to Scybale in the Moretum, returning to and affirming the significance of Haley’s initial treatment. Bellei’s piece emphasizes Haley’s right to make an interventionist translation which redresses both modern and ancient prejudices #AncientBlackness https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/1/article/925502/pdf

[9] There has been a history of classical scholarship viewing representations of blackness as representations of enslavement, projecting the history of transatlantic slave trade onto Greco-Roman antiquity. By this view, slavery is the fate of blackness #AncientBlackness https://bsky.app/profile/opietasanimi.com/post/3lheakufoq22o

Representations of black people in antiquity does not automatically amount to representations of slavery. Yet Greeks and Romans were enslavers, and they did enslave peoples whom they viewed to be “foreign” or “external” to them #AncientBlackness

There was an ancient belief that “enslavable” peoples deserved to be converted into “animate objects” or “tools” (Aristotle Politics 1.2.4, Varro Rust. 1.17.1). Emily Greenwood (2022) has recently modeled a scholarly mode which does not simply agree to ancient theories of enslavement #AncientBlackness https://muse.jhu.edu/article/862240/pdf

Ancient theories of enslavement viewed a wide range of peoples as “enslaveable.” Aristotle’s belief in natural slavery (i.e., some people “deserved” to be free; others “deserved” to be slaves) granted the right to enslave to the appropriately civilized man #AncientBlackness

[10] Within this framework, many different ethnic and racial “others” were viewed as enslaveable. By the Roman era, we find Cicero repeatedly naming different peoples as born for enslavement (e.g., Prov. cons. 10); claiming freedom as exclusive to Romans (Phil. 6.19; cf. Phil.10.20) #AncientBlackness

In recent posts, we have examined references to enslaved and formerly enslaved black figures: e.g., Scybale in the Moretum; Suetonius’ description of the African poet, Terence. Enslaved black characters do appear somewhat regularly in Latin literature #AncientBlackness

E.g., Petronius’ depiction of Trimalchio’s dinner in the Satyricon (34.4) included enslaved Aethiopian attendants. Later in the Satyrica (102.13), Petronius refers to “slave Aethiopians” (servi Aethiopes) during his staging of a conversation between Encolpius and Giton #AncientBlackness

Debra Freas (2024) has recently discussed representations of blackness in Petronius, contextualizing these passages within the history of scholarship on ancient race #AncientBlackness https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/1/article/925499/pdf

There are also artistic representations of enslaved black folk, e.g., the “figure of a seated African youth” in the Boston MFA from the Roman era which chillingly depicts the chaining of an enslaved youth #AncientBlackness https://collections.mfa.org/objects/151115/figure-of-a-seated-african-youth?ctx=4c2c5934-4777-4c87-8909-00c4af2bb5ff&idx=116

[11] Phillis Wheatley Peters was the 1st poet of what came to be the African American tradition. Peters was enslaved in West Africa when she was 7 or 8 years old and sold to the Wheatley family in Boston, where she wrote classicizing poems whose publication would lead to her freedom #AncientBlackness

Phillis Wheatley Peters’ Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773) has a now iconic image of the poet making compositions at her writing desk https://digital.tcl.sc.edu/digital/collection/pwp/id/5 #AncientBlackness

The poet has long been known as Phillis (or Phyllis) Wheatley. But In her final public statement (Sept. 1784), a proposal to publish a second volume of poetry, the poet referred to herself as “PHILLIS PETERS, formally PHILLIS WHEATLEY.” #AncientBlackness

Scholars have increasingly taken this statement as indication that she wished to be known as Phillis Peters. Honorée Fanonne Jeffers’ The Age of Phillis (2020) is dedicated to “Phillis Wheatley Peters.” #AncientBlackness

Zachary McLeod Hutchins (2021) has forcefully argued for using the name she identified with #AncientBlackness https://www.jstor.org/stable/27081952

The name “Phillis Wheatley” is itself a record of the processes of mass slavery: “Phillis” was the name of the slave ship which brought her to America, “Wheatley” the name of the family which enslaved her; see Sharpe 2016, 43–4. We do not know the poet’s original name. #AncientBlackness https://read.dukeupress.edu/books/book/4/In-the-WakeOn-Blackness-and-Being

That Peters’ primacy–her “firstness”–as an African American poet was the result of the depredations of the transatlantic slave trade was described by June Jordan as “the difficult miracle of Black poetry in America.” #AncientBlackness https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/68628/the-difficult-miracle-of-black-poetry-in-america

[12] Phillis Peters’ poetry is classicizing, i.e., it draws on Greek and Roman literary precursors. Scholars of Black Classicism have particularly focused on “To Maecenas” and “Niobe” #AncientBlackness

Peters was responding to a general 18th c interest in neoclassicism, but she also knew Latin: Peters’ knowledge of Latin is referenced in the prefatory letter to the collection composed by her enslaver, John Wheatley (Nov. 14, 1772) #AncientBlackness

As Emily Greenwood (2011, 174–5) has shown, Peters’ deployment of allusive and double meanings through the use of Latin (“error” as wandering, rather than simply “mistake”) shows a sophisticated understanding of the ancient language #AncientBlackness https://academic.oup.com/book/11766/chapter-abstract/160796901?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Peters’ wrestling with problem of classicism led to a history within the Black critical tradition of viewing her neoclassicism as a merely derivative capitulation to white oppression. Greenwood ^ addresses this difficulty, and the repeated motifs of “mimicry” adduced to the poet #AncientBlackness

Amidst this tradition, the contemporary Black feminist poet, Alexis Pauline Gumbs (2018, 122) views Peters’ excellence as independent of circumstance: #AncientBlackness

For Phillis.

Gumbs 2018: 122

what she needed was the heat. not the cute little desk in the portrait. not the windowed room looking out on Cambridge, not the white mother mistress to believe in her. what she needed was the heat, and without it she died. and it was the crossing that stole from her her own lungs. ocean miles away from the first heat that held her. knots in her chest ever tightened. her own breath forever linked to the oxygen tank of western inspiration. her Jesus like a breathing tube plugging her open nose. wherever she was she would have drunk knowledge like a whale. processed poetry with her rushing heart. wherever she was her every breath was made for prayer. and she was here. so this is what it looked like.

[13] Phillis Wheatley Peters’ “To Maecenas” is the first poem in the 1773 collection. Its title refers to Maecenas (68-8 BCE), the confidant of Augustus and literary patron of Vergil and others. The poem meditates on the nature of poetic inspiration #AncientBlackness

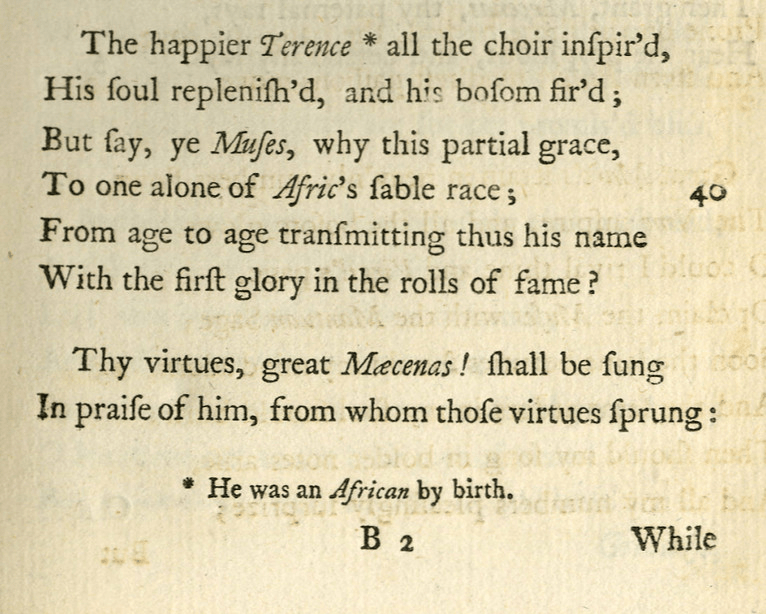

In this poem, Peters invokes Publius Terentius Afer (i.e., Terence the African) as a poetic ancestor. At the bottom of the page, the asterisk beside Terence’s name is answered by an explanatory note: “*He was an African by birth” #AncientBlackness

As we’ve already noted, Suetonius’ biography of Terence identified him as a black man from Carthage who had been enslaved and brought to Rome, where he was freed. Like Peters, he found freedom through poetic talent. She made that connection explicit. #AncientBlackness

The note in Peters’ “To Maecenas” (i.e., “He was African by birth”) closely mirrors–or paraphrases–the opening words of Suetonius’ biography: Publius Terentius Afer, Carthagine natus, “Publius Terentius the African, born at Carthage.” #AncientBlackness https://bsky.app/profile/opietasanimi.com/post/3li3qea42lk23

Cook and Tatum (2010, 19–20) also suggest that the second edition of George Colman’s translation of Terence (vol. 1: 1766, vol. 2: 1768), which included a translation of Suetonius’ Life of Terence, would have been accessible to Peters in Boston. #AncientBlackness https://www.google.com/books/edition/African_American_Writers_Classical_Tradi/U32I2Lz3voIC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=cook+and+tatum&printsec=frontcover

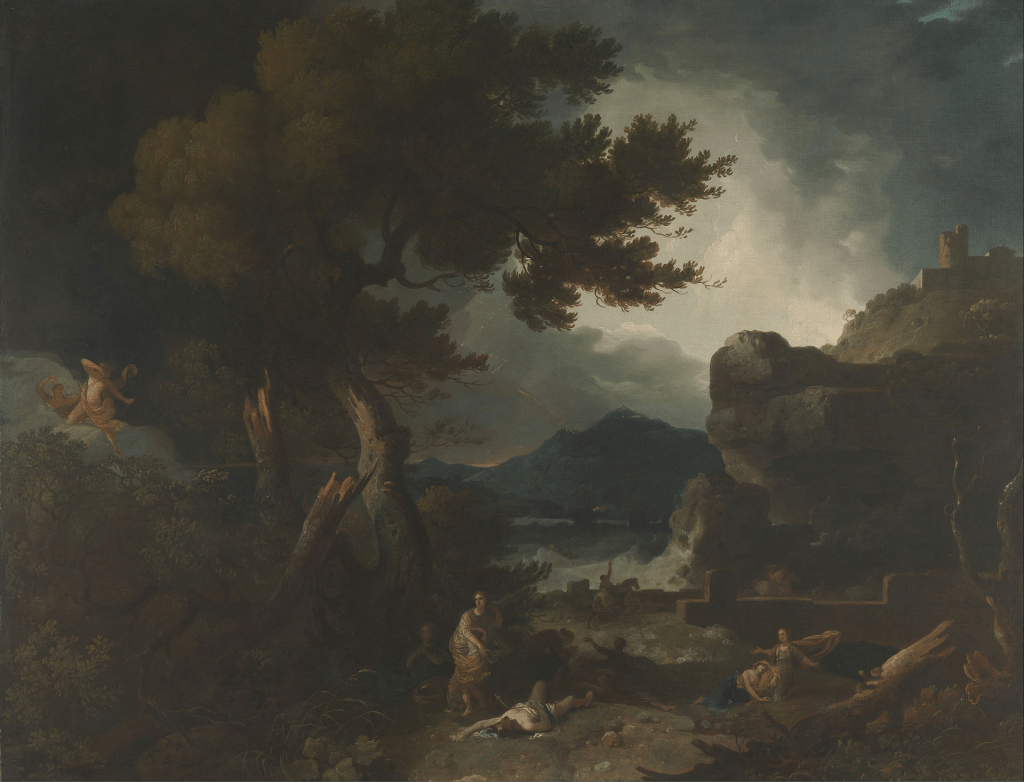

Another classicizing poem which has received scholarly attention is Peters’ Niobe poem: “Niobe In Distress For Her Children Slain By Apollo, From Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Book VI. And From A View Of The Painting Of Mr. Richard Wilson” #AncientBlackness http://www.phillis-wheatley.org/niobe-in-distress-for-her-children-slain-by-apollo/

As the title ^ demonstrates, Peters’ poem responds to Ovid’s Metamorphoses but also a contemporary painting by the Welsh painter, Richard Wilson: “The Destruction of Niobe’s Children” (1760) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Destruction_of_the_Children_of_Niobe#/media/File:Richard_Wilson_-_The_Destruction_of_Niobe’s_Children_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg

Niobe was an ancient mother whose children are murdered by gods, and who becomes a symbol of both rage and grief. Peters herself would lose three children and eventually die in childbirth. As such the poem has been read in connection to Black motherhood and the grief of enslavement #AncientBlackness

The Niobe poem = discussed by Tracey Walters in African American Literature and the Classicist Tradition (2007), Nicole Spigner, “Phillis Wheatley’s Niobean Poetics” (2001), drea brown, “’How Strangely Changed’: Phillis Wheatley in Niobean Myth and Memory, an Essay in Verse (2024)” #AncientBlackness

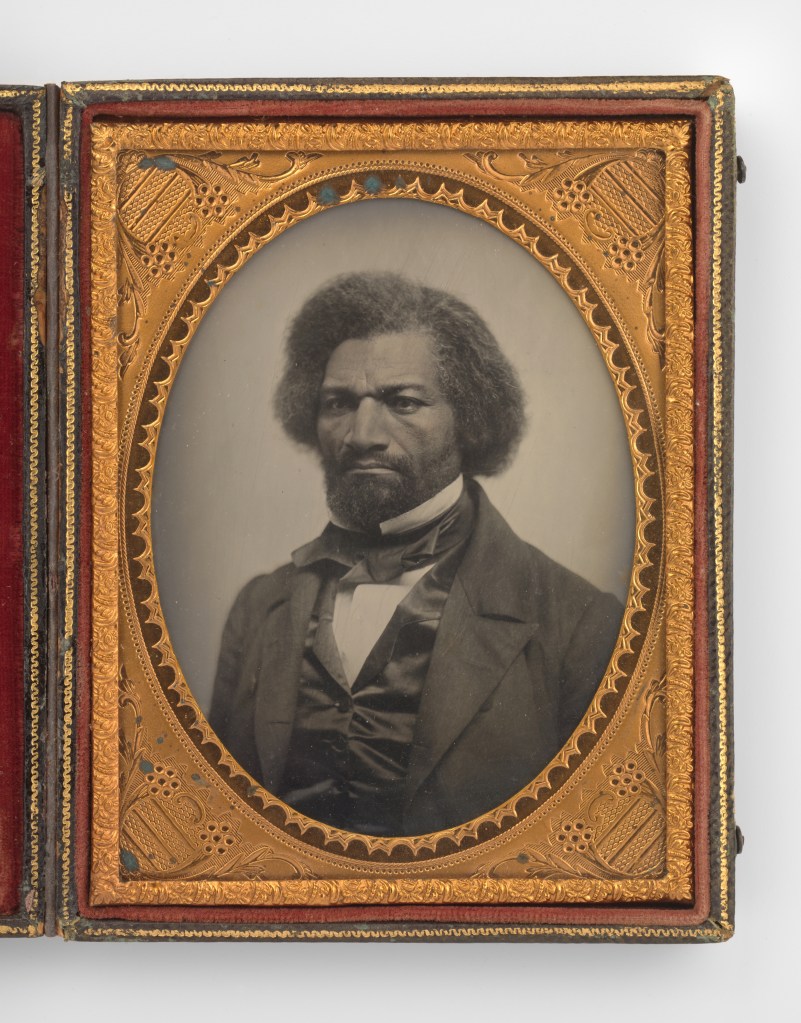

[14] The American abolitionist, statesman, and orator, Frederick Douglass (c. 1818-1895), chose February 14 as his birthday, which is why #BlackHistoryMonth is celebrated in February #AncientBlackness https://www.si.edu/object/frederick-douglass%3Anpg_NPG.74.75

Douglass escaped from enslavement in Maryland and became a national leader of the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts and New York. He was famed for his oratory and antislavery writings #AncientBlackness

In 1910, H. Cordelia Ray would write a poem commemorating Douglass as the Cicero of the African American tradition:

“Our Cicero, and yet our warrior knight,

Striving to show mankind might is not right!

He saw the slave uplifted from the dust,

A freeman!” #AncientBlackness

In Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845: 39), Douglass recalled getting hold of a copy of Caleb Bingham’s The Columbian Orator (1797) at a crucial moment #AncientBlackness

I was now about twelve years old, and the thought of being a slave for life began to bear heavily upon my heart. Just about this time, I got hold of a book entitled “The Columbian Orator.” Every opportunity I got, I used to read this book. Among much of other interesting matter, I found in it a dialogue between a master and his slave. The slave was represented as having run away from his master three times. The dialogue represented the conversation which took place between them, when the slave was retaken the third time. In this dialogue, the whole argument in behalf of slavery was brought forward by the master, all of which was disposed of by the slave. The slave was made to say some very smart as well as impressive things in reply to his master – things which had the desired though unexpected effect; for the conversation resulted in the voluntary emancipation of the slave on the part of the master.

Douglass 1845: 39

A translated excerpt of Cicero’s Catilinarians (1.31–33, i.e. the end of the speech) appeared in Caleb Bingham’s “The Columbian Orator” (1797), a wildly popular text—200,000 copies were sold by 1832 #AncientBlackness

The dialogue which Douglass praised, in which a slave is able to persuade his master to free him, identified in the system of rhetoric an emancipatory power that went beyond the classical tradition. #AncientBlackness

[15] Reverend Peter Thomas Stanford (c. 1858-1909) was an activist and minister who lived in America, Canada, and England. His “The Tragedy of the Negro in America” (1897) narrativizes histories of enslavement from 7th c. BCE to 19th c. CE #AncientBlackness https://images.nypl.org/index.php?id=1232539&t=w

Kelly Dugan (2024) has recently discussed Rev. Stanford’s The Tragedy: the white paternalism of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s preface; Stanford’s use of classical, biblical references, ancient rhetoric to argue for the sanctity of Black life #AncientBlackness https://ancienthistorybulletin.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Dugan-Res-Diff-1.1-2024-30-50-.pdf

Rev. Stanford quotes the ancient historian Herodotus (4.42), who describes King Necho’s command over Phoenician ships which led to the discovery of Libya (i.e., “Africa”) #AncientBlackness https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Tragedy_of_the_Negro_in_America/780xAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1

Dugan 2024: 42: “In citing Herodotus, Rev. Stanford not only “proved” the credential of his own education, but, importantly, demonstrated the presence of Africa in antiquity at a time when Africa as a site of cultural or intellectual production was consistently denied.” #AncientBlackness

Rev. Stanford was a Christian minister, and his “Tragedy” (1897) uses biblical quotations to argue against hypocrisy of Christian enslavers. Stanford quotes Matthew 6:24 “Ye cannot serve God and Mammon” (1897: 20) (mammon = “wealth” [debated etymology]); see Dugan 2024: 43 #AncientBlackness

[16] For today’s contribution to #AncientBlackness, I’m posting the online catalogue for “Flight into Egypt” exhibit rn on display at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. An incredible collection of Black thinkers, artists, and scholars engaging ancient Egypt. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/flight-into-egypt-black-artists-and-ancient-egypt-1876-now/exhibition-objects

It’s an incredibly rich exhibit which explores the deep ties between Egypt, Africa, African diaspora, and America. Well worth exploring the online catalogue if, like, me you can’t make it in person #AncientBlackness https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/flight-into-egypt-black-artists-and-ancient-egypt-1876-now/exhibition-objects

Also very proud to see that my colleague here at UCLA, Solange Ashby, has her book included in the exhibit! “Calling Out to Isis: The Enduring Nubian Presence at Philae” (2020) #AncientBlackness https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/flight-into-egypt-black-artists-and-ancient-egypt-1876-now/exhibition-objects

In 2021, Solange Ashby did an interview with Atlas Obscura where she described her research on ancient Nubia, which included her reflections on Egyptology’s derisiveness of Nubian studies and the difficult path to PhD within the discipline #AncientBlackness https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/ancient-africa-queens-nubia

[17] William Sanders Scarborough (1852-1926), born into slavery, is considered the first African American classical scholar. He served as president of Wilberforce University between 1908 and 1920 and wrote a popular ancient Greek textbook #AncientBlackness https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:William_Sanders_Scarborough_by_C._M._Bell_-_1903_(cropped).jpg

Scarborough’s ancient Greek textbook, “First Lessons in Greek,” was published in 1881. Following Richard Greener and Edward Wilmot Blyden, the 1st African Americans to be members of American Philological Association, he was an APA member for life #AncientBlackness https://dbcs.rutgers.edu/all-scholars/9098-scarborough-william-sanders

In 2019, Kirk Ormand interviewed Michele Ronnick on Scarborough’s classical scholarship. Ronnick discusses his contributions alongside contemporary African American scholars such as Anna Julia Cooper #AncientBlackness https://www.classicalstudies.org/scs-blog/trettonplace/blog-celebrating-scholarship-ws-scarborough-and-contributions-african

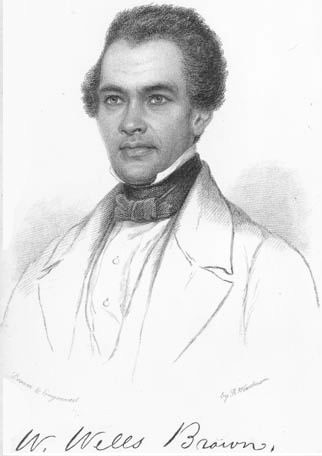

[18] William Wells Brown (1814-1884) was an abolitionist, novelist, playwright, and historian. Like Douglass, he was born into slavery and escaped to freedom. Brown’s “Clotel” (1853) is considered the first novel written by an African American writer #AncientBlackness https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Wells_Brown#/media/File:William_Wells_Brown.jpg

In The Black Man: His Antecedents, His Genius, and His Achievements (1863), William Wells Brown traces the origin of Black culture to ancient Rome. Brown also discusses ancient Roman enslaving practices, including evidence of contempt for ancient Britons (p34) #AncientBlackness https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Black_Man/pmNs5RcIjWEC?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=Cicero

Thousands of the conquered people were then sent to the slave markets of Rome, where they were sold very cheap on account of their inaptitude to learn. This is not very flattering to the President’s ancestors, but it is just. Caesar, in writing home, said of the Britons, “They are the most ignorant people I ever conquered. They cannot be taught music.” Cicero, writing to his friend Atticus, advised him not to buy slaves from England, “because,” said he, “they cannot be taught to read, and are the ugliest and most stupid race I ever saw.” I am sorry that Mr. Lincoln came from such a low origin; but he is not to blame. I only find fault with him for making mouths at me.

Brown 1863: 34

Brown was lecturing in England when the Fugitive Slave Law (1850) was passed in America. As this law aimed at his capture and re-enslavement, he stayed in Europe where he traveled for several years, composing an accompanying travel literature #AncientBlackness

Brown’s “The American Fugitive in Europe. Sketches of Places and People Abroad” (1855) describes his visit to a number of cultural sites, including the British Museum (p113) #AncientBlackness

https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_American_Fugitive_in_Europe/OaAvAAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1

I have devoted the past ten days to sight-seeing in the metropolis, the first two of which were spent in the British Museum. After procuring a guide-book at the door as I entered, I seated myself on the first seat that caught my eye, arranged as well as I could in my mind the different rooms, and then commenced in good earnest. The first part I visited was the gallery of antiquities, through to the north gallery, and thence to the Lycian room. This place is filled with tombs, bas-reliefs, statues and other productions of the same art. Venus, seated, and smelling a lotus-flower which she held in her hand, and attended by three Graces, put a stop to the rapid strides that I was making through this part of the hall. This is really one of the most precious productions of the art that I have ever seen.

Brown 1855: 113

[19] H. Cordelia Ray (1852-1916) was a Black poet and teacher, the child of notable abolitionists, Charlotte Augusta Burroughs and Charles B. Ray. She wrote poems on Pompeii, classical sculpture, and rewrote Ovid’s tale of Echo and Narcissus #AncientBlackness

Ray’s poem, “Listening Nydia,” renders a scene from Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s hugely popular novel “The Last Days of Pompeii” (1834) into verse. The subject is Nydia, a blind flower seller. #AncientBlackness https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/listening-nydia

Ray also wrote a poem on the ancient statue of Aphrodite known as the Venus de Milo. Ray’s engagement is just one in a long tradition of African American women writers and artists engaging with ancient Venus #AncientBlackness https://poets.org/poem/venus-milo

We can look forward to Grace McGowan’s in-progress book, “Venus Worked in Bronze: African American Women Writers and Classical Beauty Myths,” which argues that Black women have reclaimed Venus to influence and critique American beauty culture #AncientBlackness https://gracemcgowan.com/#:~:text=Grace’s%20current%20book%20project%2C%20“Venus,and%20critiqued%20American%20beauty%20culture

Ray’s poem, “Echo’s Complaint,” retells the story of Echo and Narcissus most famously dramatized by Ovid in Metamorphoses Book 3. Ovid is one of the favored ancient poets of Black women poets #AncientBlackness https://scalar.lehigh.edu/african-american-poetry-a-digital-anthology/h-cordelia-ray-poems-full-text-1910

Ray is perhaps most famous today for her poem, “Lincoln,” which read at the unveiling of the Emancipation Memorial in Washington DC in April 1876. We’ve already noted that she also wrote an ode to Frederick Douglass #AncientBlackness https://bsky.app/profile/opietasanimi.com/post/3li5ob5apws2j

For a recent study of Ray’s engagement with classicism, see Heidi Morse’s 2017 article #AncientBlackness https://muse.jhu.edu/article/662906

[20] Charles Chesnutt (1858-1932) was an author, essayist, political activist, and lawyer, best known for his novels and short stories. Chesnutt was the child of Andrew Chesnutt and Ann Maria Sampson both “free persons of color” from North Carolina #AncientBlackness https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_W._Chesnutt#/media/File:Charles_W_Chesnutt_40.jpg

Image: Wikimedia, Public Domain.

Chesnutt wrote a number of short stories on classical themes. In “The Roman Antique” (1889), the narrator meets an older Black man in Washington Square who recalls fighting with Julius Caesar in Gaul #AncientBlackness

https://chesnuttarchive.org/item/ccda.works00020

Chesnutt’s “The Origin of the Hatchet Story” (1889) is a visceral retelling of the euphemized tale of George Washington and “Little Hatchet,” resituating the story by placing it in ancient Egypt with Rameses III and IV as protagonists #AncientBlackness https://chesnuttarchive.org/item/ccda.works00021

For a study of Chesnutt’s Black classicism, see ch 3 of John Levi Barnard’s (2017) “Empire of Ruin” #AncientBlackness https://www.google.com/books/edition/Empire_of_Ruin/ubM1DwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=empire+of+ruin&printsec=frontcover

[21] Edmonia Lewis (1844-1907) was the first sculptor of African American and Native American descent to be recognized internationally. Her father was Black, and her mother was Chippewa (Ojibwa) Indian #AncientBlackness https://americanart.si.edu/artist/edmonia-lewis-2914

Image: Smithsonian, Public Domain.

In 1859, Lewis attended Oberlin College in Ohio, which was one of the 1st schools to accept women and Black students. Lewis became interested in fine arts, but was forced to leave the school before graduation due to racist accusations against her #AncientBlackness

Lewis then traveled to Boston where she worked as a professional artist, studying sculpture and producing portraits of those who had fought against slavery. In 1865, she moved to Rome alongside American women sculptors, and began to sculpt in marble #AncientBlackness

Lewis sculpted a number of subjects, including biblical scenes, Native American figures, scenes of anti-slavery, and also classicizing pieces.

Left: Old Arrow Maker (1866)

Right: Young Octavian (c. 1873) #AncientBlackness

https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/old-arrow-maker-14629

https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/young-octavian-14633

Lewis’ “The Death of Cleopatra” (1876) shocked contemporary audiences for its realistic depiction of death, exhibited to great acclaim at the Centennial Exhibition in 1876. The sculpture was eventually used to mark a horse’s grave at a racetrack #AncientBlackness https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/death-cleopatra-33878

In 2020, Margaret and Martha Malamud published an article on Edmonia Lewis’ Cleopatra, discussing the sculpture’s dialogue with the Cleopatra of William Wetmore Story #AncientBlackness https://muse.jhu.edu/article/815654

Lewis’ Cleopatra also seems to have a role in Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich’s “Cleopatra at the Mall” (2024) #AncientBlackness https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/909996

[22] Anna Julia Cooper (1858-1964) was one of the most prominent African American scholars in US history: a writer, educator, sociologist, orator, Black liberation activist, Black feminist leader #AncientBlackness https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c8/A_J_Cooper.jpg/1024px-A_J_Cooper.jpg

Cooper was born into slavery in North Carolina. When she was 9yo, she started attending St. Augustine’s Normal School and Collegiate Institute in Raleigh, which had been founded to train teachers to educate the formerly enslaved and their families #AncientBlackness

At St. Augustine’s, Cooper studied Latin, French, Greek, English literature, mathematics, and science. Cooper also fought to take classes which had been reserved exclusively for men #AncientBlackness

After completing her studies at St. Augustine’s, she stayed on as a teacher. In 1883-1884, she taught classics, modern history, English, and music. In 1885-1886, she is listed as “Instructor in the Classics, Modern History and Higher English.” #AncientBlackness https://archive.org/details/catalogueofstaug18821899/page/n35/mode/1up?view=theater

Cooper attended Oberlin College, graduating in 1884. She taught briefly at Wilberforce College as well as St. Augustine’s. Cooper then earned her MA in mathematics in 1888 from Oberlin, making her one of the first two Black women to earn an MA, alongside Mary Church Terrell #AncientBlackness

In 1890-91, Cooper published a speech, “The Higher Education of Women,” which argued the benefits of Black women being trained in classical literature, in which she discussed Socrates and Sappho #AncientBlackness https://speakingwhilefemale.co/education-cooper1/

In this piece, Cooper anticipated by a decade the arguments which W. E. B. Du Bois would make regarding the spiritual utility of classical education for African Americans in “The Souls of Black Folk” (1903). Du Bois’ contribution has historically been prioritized by modern scholars #AncientBlackness

In 1900, Cooper traveled to Europe to take part in the First Pan-African Conference in London. During this trip, she also visited Scotland and England, and went to Paris for the World Exposition. She visited Rome, Naples, Venice, Pompeii, Mt. Vesuvius, and Florence #AncientBlackness

In 1892, Cooper formed the Colored Women’s League in Washington, DC, with Helen Appo Cook, Ida B. Wells, Charlotte Forten Grimké, Mary Jane Peterson, Mary Church Terrell, and Evelyn Shaw. Around this time, Cooper began to teach Latin, math, and science at M Street High School #AncientBlackness

While principal at M Street High School, Cooper published her first book, “A Voice from the South: By a Black Woman of the South” (1892), delivered speeches advocating for civil rights and women’s rights. “A Voice from the South” is often seen as the earliest Black feminist text #AncientBlackness

Here’s a link to the text of Anna Julia Cooper’s “A Voice from the South” (1892): https://docsouth.unc.edu/church/cooper/cooper.html #AncientBlackness https://docsouth.unc.edu/church/cooper/coopefp.jpghttps://docsouth.unc.edu/church/cooper/coopetp.jpg

In 2014, Heidi Morse completed her dissertation from UCSC, “Minding ‘Our Cicero’: 19th century African American Women’s Rhetoric and the Classical Tradition,” demonstrating Cooper’s interest in Cicero: in particular, her interest in Cicero’s “De Oratore” #AncientBlackness https://uchri.org/awards/minding-our-cicero-nineteenth-century-african-american-womens-rhetoric-and-the-classical-tradition/

At the age of 56, Cooper began her PhD at Columbia University, but interrupted her studies when she adopted her half-brother’s children in 1915. She later completed her PhD at the University of Paris-Sorbonne with a thesis on France’s “attitude” to slavery between 1789 and 1848 #AncientBlackness

[23] W. E. B. Du Bois (1868-1963), born #otd, was an American sociologist, historian, and later Pan-Africanist civil rights activist. He died in Accra, Ghana. He was a Classics professor at Wilberforce University, and the first African American to earn his PhD from Harvard #AncientBlackness

Du Bois was deeply engaged with classical texts over the course of his life, not simply during his brief time as a Classics professor. As Maghan Keita (2000) has discussed, he was deeply interested in Snowden’s research on black people in antiquity #AncientBlackness https://www.google.com/books/edition/Race_and_the_Writing_of_History/fnylq8hkVbYC?hl=en&gbpv=0

In “The Souls of Black Folk” (1903), Du Bois made a number of references to ancient texts. In “Of the Meaning of Progress,” Du Bois famously describes trying to teach rural Black children by putting “Cicero pro Archia Poeta into the simplest English with local applications” #AncientBlackness

When the Lawrences stopped, I knew that the doubts of the old folks about book-learning had conquered again, and so, toiling up the hill, and getting as far into the cabin as possible, I put Cicero “pro Archia Poeta” into the simplest English with local applications, and usually convinced them—for a week or so.

Du Bois 1903, “Of the Meaning of Progress”

Mathias Hanses discussed Du Bois’ engagement with Cicero’s Archias speech in a 2019 article. We can also look forward to Hanses’ forthcoming book, “Black Cicero: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Ancient Romans in the 19th and 20th Centuries.” #AncientBlackness https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12138-018-0476-8

Mathias Hanses and Harriet Fertik co-edited a special issue of the International Journal of the Classical Tradition, “Above the Veil: Revisiting the Classicism of W. E. B. Du Bois” (2019). Fertik is at work on a book on Du Bois and Hannah Arendt #AncientBlackness https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12138-018-0475-9

In “The Souls of Black Folk” (1903), Du Bois famously described the veil, double consciousness, the color line. “Of the training of Black Men” climaxes with invocation of ancient authors as Du Bois’ spiritual colleagues. “I summon Aristotle and Aurelius…they come all graciously” #AncientBlackness

I sit with Shakespeare and he winces not. Across the color line I move arm in arm with Balzac and Dumas, where smiling men and welcoming women glide in gilded halls. From out the caves of evening that swing between the strong-limbed earth and the tracery of the stars, I summon Aristotle and Aurelius and what soul I will, and they come all graciously with no scorn nor condescension. So, wed with Truth, I dwell above the Veil. Is this the life you grudge us, O knightly America? Is this the life you long to change into the dull red hideousness of Georgia? Are you so afraid lest peering from this high Pisgah, between Philistine and Amalekite, we sight the Promised Land?

Du Bois 1903, “Of the Training of Black Men”

Du Bois had a lyrical sensibility. His 1911 novel, “The Quest of the Silver Fleece,” combined classicism with imaginative narrative. This work has been discussed by Jackie Murray, “The Quest of the Silver Fleece: The Education of Black Medea” (2019) #AncientBlackness https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/1/article/742080/pdf

More recent studies of Du Bois’ classicism draw attention to several failings in classicists’ approach to his work: classicists tend to point to Du Bois’ early writing, euphemistically and blandly identifying references without acknowledging the political potency of his arguments #AncientBlackness

Classicists are also in danger of focusing solely on the classical references in his early work (i.e., “The Souls of Black Folk”) without recognizing how Du Bois’ attitude shifted towards larger political concerns over the course of his career, such as his Pan-Africanism #AncientBlackness

Scholars have also increasingly wrestled with the difficulties and limits of Du Bois. Although he supported women’s suffrage, his treatment of women in his life was not always positive. He didn’t for instance adequately engage the work of Anna Julia Cooper #AncientBlackness https://bsky.app/profile/opietasanimi.com/post/3liryedv2xk2g

We can also look forward to Dan-el Padilla Peralta’s forthcoming discussion of the concept of classicism, and the fraught nature of Du Bois’ own classicism in “Classicism and Other Phobias” #AncientBlackness https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691266183/classicism-and-other-phobias?srsltid=AfmBOor0gKVmwVjrVJ8-PKCLh4QzLyaEH5Tf9sbcekTvSvKuUOSpwgsC

Padilla Peralta’s new book is a development of the lectures he delivered for the W. E. B. Du Bois Lecture Series in 2022 #AncientBlackness

[24] Pauline Hopkins (1859-1930) was an American novelist, journalist, playwright, historian, and editor. Hopkins wrote among the 1st (if not the 1st) theatrical drama & detective stories by a Black writer. She made significant contributions as editor of “Colored American Magazine” #AncientBlackness

Hopkins’ “Of One Blood: Or, The Hidden Self” first appeared in serial form in “Colored American Magazine” (1902-1903), while Hopkins served as editor. “Of One Blood” tells the story of a Black medical student who travels to an Ethiopian city with Wakanda-like advanced technology #AncientBlackness

In 2021, Katherine Ouellette wrote a piece on Pauline Hopkins’ legacy which describes how racist canon formations privileged Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” or Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” over Hopkins’ original creative contributions #AncientBlackness https://www.wbur.org/news/2021/02/12/pauline-hopkins-of-one-blood-hagars-daughter

In 2021, Grace McGowan analyzed the classicism of Lizzo’s and Cardi B’s “Rumors” in context of Pauline Hopkins’ controversial editorial which argued that the models of classical beauty had been enslaved Aethiopians #AncientBlackness https://www.salon.com/2021/09/04/in-rumors-lizzo-and-cardi-b-pull-from-the-ancient-greeks-putting-a-new-twist-on-an-old-tradition_partner/

Chapter 6 of Sarah Derbew’s “Untangling Blackness” (2022) discusses Charicleia in Heliodorus’ Aithiopika alongside Pauline Hopkins’ “Of One Blood” #AncientBlackness https://www.google.com/books/edition/Untangling_Blackness_in_Greek_Antiquity/Iy9lEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=untangling+blackness&printsec=frontcover

[25] At this point it’s time to turn, at last, to Martin Bernal’s “Black Athena” (Vol. 1: 1987, Vol 2.: 1991, Vol. 3: 2006). Bernal argued the “Afro-Asiatic” roots of Greek culture, but as this thread has shown, Black scholars had already been doing so for a century #AncientBlackness

In 2018, Elena Giusti interviewed Sarah Derbew, who at that time drew attention to the fact that Black scholars such as Drusilla Dunjee Houston, Engelbert Mveng, and Cheikh Anta Diop had already made arguments similar to Bernal’s #AncientBlackness

https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/classics/intranets/students/modules/africa/interview/sarahderbew/

SD It is always important to be mindful of one’s own positionality. So I use the same critical lens that we’re taught to use in Classics to read both Martin Bernal and Heliodorus. We are not exempt from it just because we’re writing in the present. The fact that Bernal was a Cambridge trained tenured Professor very much affects the perceived legibility of his arguments. Before him, in 1926, an African American historian, Drusilla Dunjee Houston, wrote about similar topics, just like Engelbert Mveng, a Cameroonian Jesuit priest whose 1972 dissertation examined the presence of black people in ancient Greek literature, or Senegalese anthropologist Cheikh Anta Diop. Somehow, arguments become more understandable when they come from a mouth that we perceive to be part of the established academy. So I do think it is important, if we decide to teach Bernal, to make sure that we situate Black Athena within a broader landscape. He is not the only one proposing these ideas.

Derbew’s 2022 book (which I’ve been citing so much for this thread) restates the points she had made in 2018, that Bernal’s privilege as a white Cambridge scholar made his remarks more legible to classicists, who had ignored the scholars listed above^ #AncientBlackness https://www.google.com/books/edition/Untangling_Blackness_in_Greek_Antiquity/Iy9lEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

In 2018, Denise McCoskey published an Eidolon article which drew attention to the methodological problems of Bernal’s work, while also documenting classicists’ panic with the idea that Greece did not emerge fully formed as if from the forehead of Zeus #AncientBlackness https://eidolon.pub/black-athena-white-power-6bd1899a46f2

Amidst the methodological problems of Bernal’s work was his reliance on an “invasion” model. McCoskey ^ notes Bernal’s endorsement of the so-called “Dorian invasion” (Vol 1, p. 21), a white supremacist theory which attributes Greek genius to Germany #AncientBlackness

In 2018, Rebecca Futo Kennedy also published the following piece which contextualizes the intellectual and ideological commitments of the “Dorian invasion” theory #AncientBlackness https://medium.com/@rfutokennedy/the-dorian-invasion-and-white-ownership-of-classical-greece-340b7a5d17b9

Bernal’s work was flawed but reactionary response to it by classicists demonstrated the disciplinary panic over its potential to “darken” the discipline. Mary Lefkowitz infamously responded with “Not Out of Africa” (1996) whose cover emphasizes white anxiety over ancient blackness #AncientBlackness

McCoskey’s 2018 piece, as well as her earlier 2012 book, “Race: Antiquity & Its Legacy,” also discuss Bernal’s overall carelessness in naming his book “Black” Athena. He chose “Blackness” to sell the book–he wasn’t actually interested in ancient blackness #AncientBlackness https://bsky.app/profile/opietasanimi.com/post/3lj47etxu5s2q

In 2024, Mathura Umachandran and Marchella Ward also discussed Bernal as part of a long-standing disciplinary commitment to positivism and Eurocentrism in their intro to the CAWS volume #AncientBlackness https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/oa-edit/10.4324/9781003222637-2/towards-manifesto-critical-ancient-world-studies-mathura-umachandran-marchella-ward?context=ubx&refId=08958e3a-5479-4c9f-bbad-e295a92f00f7

[26] Gwendolyn Brooks (1917-2000) was an American poet, author, and teacher. She won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry on May, 1950, for “Annie Allen,” making her the first African American writer to win a Pulitzer #AncientBlackness

Classical allusions appear throughout Brooks’ poetry, with references to Greece, Rome, Egypt, and biblical scenes. Like Phillis Wheatley Peters and H. Cordelia Ray, Brooks showed a deep interest in form. In fact Brooks’ prosody was considered difficult and alienated some readers #AncientBlackness

Brooks was also steeped in a tradition of American classicism: James Weldon Johnson (author of “The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man,” 1912) encouraged her to read T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and E. E. Cummings #AncientBlackness

But Brooks was also particularly rooted in the tradition of Black classicism: her work has echoes of Countee Cullen (who wrote a “Medea”) and Langston Hughes, whom she had met through her mother. Brooks’ mother called her “lady Paul Laurence Dunbar” #AncientBlackness

Brooks learned Latin, and translated parts of Vergil’s Aeneid into English in high school. She also wrote a mock lament for Vergil in 1934. On Brooks and Vergil, see Michele Ronnick 2010 #AncientBlackness https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781444318050.ch26

Oh, Vergil, dust and ashes in thy grave

Brooks 1934

Wherever thy grave sepulchered may be

Forgive me this small speech, wherein I rave

That thou didst ever live to harass me.

Oh, not that I do not appreciate

The mild, concordant beauty of your lines—

But I am puzzled by them; I translate,

And every word seems but a set of signs.

Brooks’ collection, “Annie Allen” (1949), for which she won a Pulitzer in 1950, contains an epic poem called “The Anniad,” which used an experiment form of “sonnet-ballad” described by critics as “technically dazzling.” But critics also found its classical references inaccessible #AncientBlackness

In 1967, Brooks attended a conference at Fisk University, where she encountered younger, more radical Black writers, who viewed classical references as an assimilation into whiteness. After this, Brooks increasingly abandoned neoclassicism as a poetic technique #AncientBlackness

In her 1996 autobiography, “Report from Part Two,” Brooks reflected on the whiteness of the classical tradition: “‘Nine Greek Dramas’… White white white. I inherited these White treasures.” #AncientBlackness

[27] Rita Dove (b. 1952) is an American poet and essayist. From 1993-1995, she served as Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, the first African American to receive such an appointment #AncientBlackness https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rita_Dove#/media/File:Rita_Dove_by_Gage_Skidmore.jpg

Dove is the second African American writer to receive the Pulitzer for Poetry, which she received for her poem “Thomas and Beulah” in 1987. Gwendolyn Brooks had been the first. She served as Poet Laureate of Virginia from 2004 to 2006 #AncientBlackness

Classical references can be found throughout Rita Dove’s poetry, from short poems like “Pithos” to her verse play adaptation of Sophocles’ Oedipus, “The Darker Face of the Earth” (1994) #AncientBlackness

In an interview with Therese Steffen (1997), Dove reflected on her interest in selection and recombination of cultural artefacts (including the classical) to which the poet felt an an emotional or ancestral connection, praising Ishmael Reed and Ai Ogawa for cultural eclecticism #AncientBlackness

In this interview ^, Dove said: “[Ishmael] Reed doesn’t just mention hoodoo for flash; he mixes the arcane perceptions of voodoo into the text. Ai writes from all her experiences, all of her heritages.” For Dove, classicism became a cultural heritage #AncientBlackness https://www.jstor.org/stable/2935376?casa_token=IgAY2MB0IH4AAAAA%3AlgtBjsquZaYIof36Od8hznWfMtU037JLx49Un2HRaUQoBvVjhW0z1Hm5DWfKdc9KIGuzGnenBMjVBt8EtT_Qvg2GXU0c0IlpJLOZ6UVKfaD48vpWu5DW

In the 90s, Dove distanced herself from the contemporary categorization process that wished to label her as a “Black writer.” Yet she identified the mechanism of ancestral voiding enacted by the middle passage as the site of literary origins for the African diaspora (1997: 13) #AncientBlackness

It’s another way of improvising, rooted in the African American experience of being brought over the Atlantic on slave ships and arriving in a terrifying foreign country, not knowing the language, not knowing what happened to your parents or children. How do you survive in such a situation? Well, you make do—cherish what you remember, and absorb what you can of the new cultures, making them part of your own culture. Think of the great jazz musicians, like Coltrane, who could take a syrupy song like ‘My Favourite Things’—sung by Julie Andrews in The Sound of Music—and make it jazz. He actually transforms the song; it becomes part of his music. And that’s been done in African American literature.

Dove, interviewed by Steffen 1997: 13

In contrast to Harold Bloom, whose brutalist theory of influence Dove publicly criticized, the poet did not see herself in an oedipal relationship with literary precursors (i.e. killing them to take their place), but instead held disparate parts together as an assembling #AncientBlackness

In 1998, Dove published the following in the Boston Review (31). On Bloom and Dove, see Goff and Simpson 2007: 173-174 https://academic.oup.com/book/2764/chapter-abstract/143267032?redirectedFrom=fulltext #AncientBlackness

Let the critics shriek; I am writing my poems. I am not writing for the approval of Harold Bloom, although I do not mind sharing with him some of my literary company, like Shakespeare and Keats and Whitman and Dickinson. However, as far as some other favorite company of mine is concerned—from Sappho to Hughes to Hayden and Rukeyser—I happily leave the narrow‐minded praetorians outside the gates in their dusty armor.

Dove 1998

Dove’s “Arrow” (1987) also dramatizes the physical stress experienced by Dove and her students listening to a reading of Aristophanes’ Thesmophoriazusae by the classicist, William Arrowsmith, who appropriated Black speech for his translation #AncientBlackness

Rita Dove’s “The Darker Face of The Earth” (1994) sets the story of Sophocles’ Oedipus on a plantation in antebellum South Carolina. This retelling reframed the incest-plot of the Greek original as a parable for racial enmeshment and miscegenation as product of American slavery #AncientBlackness

Initially conceiving the idea for “The Darker Face of the Earth” in 1979, Dove did not publish the play until 1994. It was not performed until 1996 at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Patrice Rankine discussed the play in 2013 #AncientBlackness https://www.baylorpress.com/9781602584532/aristotle-and-black-drama/

Dove’s “Mother Love” (1995) is also an extended retelling of the “Homeric Hymn to Demeter.” Chapter 5 of Tracey Walters’ 2007 treatment of Black women writers and the classics discusses “The Darker Face” and “Mother Love” #AncientBlackness https://www.google.com/books/edition/African_American_Literature_and_the_Clas/CjB9DAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

[28] For the final day of #BlackHistory month and #AncientBlackness, let’s discuss Toni Morrison (1931-2019) and her engagement with the classical tradition.

Earlier in the #AncientBlackness thread, we discussed Haley’s reading of Euripides’ “Medea” and Morrison’s “Beloved.” Haley begins with an invocation of Morrison’s warning not to view African and African American literature as meaningful only insofar as it engages classics. https://bsky.app/profile/opietasanimi.com/post/3lhjhrgt3uc2p

This warning comes from Morrison’s “Unspeakable Things Unspoken” (1988). In this lecture, Morrison describes how classics as a discipline created itself by making artificial distinctions between Greece and the world. She also writes of Greek tragedy read for supremacy #AncientBlackness https://tannerlectures.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/105/2024/07/morrison90.pdf

A large part of the satisfaction I have always received from reading Greek tragedy, for example, is in its similarity to Afro-American communal structures (the function of song and chorus, the heroic struggle between the claims of community and individual hubris) and African religion and philosophy. In other words, that is part of the reason it has quality for me—I feel intellectually at homer there. But that could hardly be so for those unfamiliar with my ‘home,’ and hardly a requiste for the pleasure they take. The point is, the form (Greek tragedy) makes available these varieties of provocative love because it is masterly—not because the civilization that is its referent was flawless or superior to all others.”

Morrison 1988: 125

Morrison studied Latin at high school and was a Classics minor at Howard University in the 1950s at which time the department was chaired by Frank Snowden. Morrison showed consistent interest in the Africanness of classics, as Roynon (2011) writes #AncientBlackness https://academic.oup.com/book/3616/chapter-abstract/144932567?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Morrison’s novels engaged classical precursors in transformative ways: Patrice Rankine (Ulysses in Black, 2006) discusses Ulysses in Morrison’s Song of Solomon; Walters (2007) discusses SoS, Beloved, and Bluest Eye #AncientBlackness https://www.google.com/books/edition/African_American_Literature_and_the_Clas/CjB9DAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

In 2013, Tessa Roynon published a monograph treating Toni Morrison’s exploration of classical traditions in ten novels, demonstrating how such allusions were put to use as transformative critique #AncientBlackness https://www.google.com/books/edition/Toni_Morrison_and_the_Classical_Traditio/qWkBAQAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Morrison’s “Beloved” (1987) took its inspiration from the historical Margaret, Garner who had fled slavery but was caught following Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Instead of returning to enslavement, Garner killed her daughter #AncientBlackness

Garner was subsequently characterized as a Medea-figure, most famously in Thomas Satterwhite Noble’s “The Modern Medea” (1867), whose image spectacularizes the death of African Americans for white audiences #AncientBlackness

https://www.loc.gov/item/99614263/

Morrison’s “Beloved” (1987) took this historical association of Garner and Medea, originally designed to spectacularize, and wrote a Medea-figure with the haunted psychology of a formerly enslaved Black woman, driven to protect her children from suffering of slavery #AncientBlackness

Morrison’s fundamental work of reconfiguration by close observation has also been used as a theoretical model for reading ancient texts. Recently, Emily Greenwood (2022) performed a close reading of Aristotle’s argument for slavery through Morrison https://muse.jhu.edu/article/862240/pdf #AncientBlackness

As my final post for the #AncientBlackness thread, let me send readers to the @eosafricana.bsky.social website, with even more information on Africana receptions of antiquity. Thanks for following along! https://www.eosafricana.org